Restoring Parents’ Confidence in International Schools

WHAT’S THE ISSUE: Thirty years ago, most capital cities around the world only had one or two international schools. It’s now not uncommon for there to be 10 or more international schools in a capital city. For local parents, one of the ‘selling points’ of investing in an international school education is that children may receive a better education and get into a good university abroad. Meanwhile, more families are relocating for work or lifestyle reasons, which is also an important contributing factor in the proliferation of international schools. But has the rise of competition improved the quality of teaching and learning in international schools? I’ve found parents who have seen 3 or more children go through the international school system find it hard to answer ‘yes’, with confidence. Restoring parental confidence in the school also appears to be a growing concern among international school staff. I believe before we can start talking about solutions, we need to try and better understand this complex problem.

RESTORING PARENTs' CONFIDENCE BY IDENTIFYING POSSIBLE ROOT CAUSES

On the one hand, in some international schools and departments, you see grade inflation (predicting higher grades than the IB cohort achieves) has led to heartbreak amongst whole cohorts of international school students. Some teachers consistently overpredict IB Diploma grades. As a result, year after year, their IB Diploma students are (mis)led to believe that they are on track for a 6 in HL Psychology, for example. Parents and students are told that is the level they are working on through feedback on essays and Parents Evenings. Yet the average results of the whole cohort on their final IB Diploma exams speaks for itself.

In others, there are school leaders who have flat out lied to prospective parents, perhaps driven by an intention of ‘making the sale’ at all costs. They lied about the average IB Diploma score of their previous graduating classes. This was done through verbal communication in meetings with prospective parents – nothing was shared publicly on the website or in writing.

I once coached an IBDP alumni whose 11th and 12th Grade IB Maths teacher, putting his feet up on the desk at the start of the lesson and his hands behind his head, pronounced, “Whether I teach the lesson today or not, you’re all going to get into a university. Your parents are rich.” The teacher inflated this student’s, as well as his classmate’s, IB Maths Report Card progress grades for the full two years of their IB Diploma experience. He gave them a false sense of security that ultimately led to most of them getting very poor marks in their final IB exams.

Both the student concerned, and his parents, gave consent for me to share this story here as they want to help raise awareness about this type of prejudice that can sometimes exist towards students who go to private schools that offer the IBO’s curriculum. These unprofessional behaviours can have serious consequences for students’ well-being and exam success. While you may be thinking ‘well this doesn’t happen in our school’…it’s worth doubling down carefully to vet teachers for more than just their credentials before offering someone a teaching job in your school. This is in the best interest of your school’s reputation, not just your students’ well-being and learning outcomes.

Another point raised by a parent I interviewed had to do with giving financial incentives to attract teachers who know what they are doing. I quote: “In most capital cities of low income developing countries, the enormous majority of secondary teachers have never worked in an IB School before. They have also not done the IB Diploma themselves. Hence, they fail to understand the experience needed and the teaching qualities required to master the IBDP curriculum, which is way more demanding than the British A-levels and American SAT curriculum. I believe teachers who went through the demanding IBDP program in their secondary education should be provided with extra pay in view of their experience and get priority in overseas IB school recruitment.”

Furthermore, another parent noted how even though the school tried to rectify this gap in IB curriculum experience and understanding by sending their new DP teachers to do the official IBO’s subject specific training, many still didn’t seem to have grasped how to accurately mark student work to identify if it was a 3, 4, 5, or 6. This became evident when two years later, all of the students who sat the final IB Diploma exams in this cohort got much lower overall IB scores than their school’s IB teachers had predicted.

The issue of recruiting and retaining good teachers with relevant credentials and experience is a major issue that I believe deserves to be openly acknowledged and discussed. Partly because doing so may help us understand why unprecedented levels of international school parents feel they are forced to start hiring private tutors in recent years. And partly because a growing disconnect seems to be developing between the image an international school projects through marketing and branding, and what goes on behind classroom doors. When there is this type of disconnect, over time, what can ensue is a gradual decline in parent’s confidence in the school among a significant enough number of parents. This can become quite a big problem for a school’s leadership team.

While some staff in international schools may only stay for a few years before they relocate to another country to start a new chapter in their international school career adventure, sometimes an IBDP alumni’s cousins and siblings are in the following IB Diploma cohort. If there is a continual stream of staff who leave behind the aftermath of unprofessional behaviour, word of mouth spreads, causing a gradual eroding of parents’ confidence in a school, long-term.

Another factor that may be contributing to a possible decline in quality of teaching may be that pay and benefits in some international schools have become less competitive over the years. This may also explain why so many teachers now work a second job after teaching hours, forced to offer tutoring services to students enrolled in other international schools as a way of supplementing their income. Some even work a third job as an IB examiner, as well as working as tutors for online IB tutoring companies in the evening and on weekends. As a result, some teachers may no longer have the financial incentive, or energy, to look after students in their day job in the way that they used to.

Add to that unprocessed chronic stress that has affected many teachers’ wellbeing and health, and by extension, their ability to be productive in their day job as an international school teacher. The chronic stress caused by the global pandemic and its negative impact on student behaviour in the classroom continue to challenge even the most experienced of teachers in schools where Social Emotional Learning and student and staff well-being are not made a high priority. Then add to that the cost-of-living crisis we are all living through, which is another source of chronic stress for people on teacher salaries. You can then start to get a sense of why a growing number of teachers may be struggling with chronic stress and well-being issues in international schools, which may in turn be affecting the quality of teaching and learning.

On the other hand, there are some who argue that the rise of private tutoring has less to do with the decline of quality of provision in international schools, and more to do with the rise of insecurities among parents about how good they are of a parent. They observe parents in their school who feel pressure to hire tutors because they feel their child’s exam results are a direct reflection of how good they are as a parent. Perhaps they worry that their child will fall behind if they are one of the few kids in the class that do not have one or more tutors. Or there may be a school culture of competition in which parents are seeing their child as an extension of themselves, using their kid’s academic success to ‘compete’ with each other, as parents. In such cases, it may help for parents to take responsibility for the way that their behaviour may be contributing to the problem.

RESTORING PARENTS' CONFIDENCE: IDENTIFYING POSSIBLE NEXT STEPS

Whatever the truth may be, the bottom line is that parents can no longer depend on a school’s published IB, IGCSE, or A Level results to ascertain how good of a school it is in this new era of international school education. The private tutoring industry is now so big that it’s hard to know, with certainty, how far a school’s externally assessed exam results can be attributed to the quality of that school’s teaching and learning.

I believe we are entering a new era where school branding, impression management, and PR are not as important for international schools as they were in the past. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to ‘brush things under the carpet’ and hope they will just go away. The more things get brushed under the carpet…the more things start to smell!

International school leaders openly discussing with each other any issues related to declining parental confidence that they are facing through a collaborative, problem-solving approach may be helpful.

What if a decline in parents’ confidence in some international schools were an opportunity for personal, professional, and systemic growth? What if it was an opportunity for a school’s senior leadership team to wonder – what needs to happen for parental confidence to be restored?

MEET ELENI

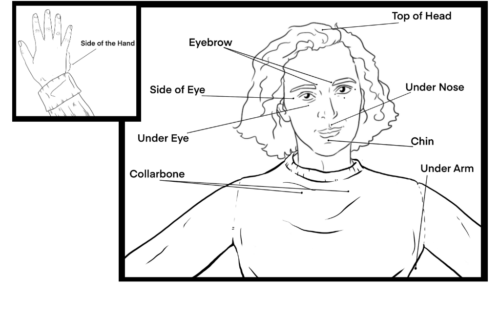

Eleni Vardaki (BA, PGCE, QTS, MEd) is an experienced secondary school teacher and EFT Tapping Coach who specializes in stress, anxiety, and academic success. She works with school and university level students who want her assistance on clearing their inner blocks to achieving their personal, career-related, or academic goals. She also leads online and in-person group sessions for staff, parent, and student well-being. Much of her experience as an Academic and EFT Coach is in working with IB Diploma students as well as undergraduate students who went to internationals schools that offered the DP program all over the world.

LEARN MORE

- “Auditing Staff Well-being in International Schools” by Kirsten Pontius

- “Relationships and Resilience” by Dr. Sue Roffey

- “Tapping for Pain Relief: Does EFT Really work?” by Eleni Vardaki

- “Hidden Struggles of International School Students: Adversity Amidst Privilege” by Tanya Crossman

- “International Teaching Jobs” by Mark Webber

- “Is Too Much Tutoring Spoiling Kids?” by Eleni Vardaki