Mock Exams, Mindfulness and Mandarins

WHAT’S THE ISSUE? One way we can teach students well-being skills is through well-being initiatives that are championed from the top. This is what’s happening in schools like the International College of Hong Kong.

And another way is through teacher leadership, by teachers like myself building well-being skills training into our classrooms through a bottom-up approach.

In this article, I share an example of how I started enriching my History teaching with mindfulness-based exercises that help students psychologically prepare for their exams…AND learn how to take their writing and higher-level thinking skills up to the next level in demanding exam conditions.

MOCK EXAMs AND REAL EXAMS

This is the story of how my Mock Exams, Mindfulness and Mandarins lesson was “born”. It all started in January 2017. Back then, I was responsible for teaching 30 IGCSE History students who were then in Year 11. If you’re unfamiliar with the British system, Year 11 is 10th Grade, in the U.S. IGCSE exams are for students aged 14-16.

January is mock exam season in the school where I worked. It was the first time students in this school experienced what it’s like sitting all three IGCSE History past papers in full. They had 5 months to go before their final exams.

Students have to revise two-year’s worth of IGCSE History content. It was a challenge. It was the first time in their lives that they had to revise so much content. They would come back to class from the challenging of-timetable mock exams period exhausted, stressed, and unable to focus. Many were stuck in a chronic state of stress.

By January 2017, I’d realized that the issue was more than a few nervous students. This was a trend. The trend was students were coming back from their mock exams unable to focus, and worried about the real exams. The penny had dropped. They were fully aware of how challenging the final exam was going to be.

Their exam-related stress was getting in the way of their learning.

STUDENT WELL-BEING: FEAR, SELF-DOUBT, and PESSIMISM

It’s a myth that the only kids who fear failure are the ones who have failed on their mock exams.

A lot of these fears come from students who are academic high-achievers.

Even if they do well in their mock exams (A*, A, B), most students still feel anxious, scared (or even terrified) of the real exam.

Here’s a list of the most common fears:

“Miss, there’s no way I’m going to finish the exam on time.”

“What if I fail?”

“How are we supposed to remember all this?”

“What if I panic and forget everything in the exam?”

“There’s no way I’m going to remember all this.”

“I have a bad memory.”

“There’s not enough time.”

“I’m not very good with time management.”

“What if I don’t finish on time?”

“This is impossible.”

“I’m going to fail.”

“Miss, I tried answering this past paper question last night and I like TOTALLY freaked out. I had NO idea how to answer it. What if that happens in the real exam??”

Now you might be thinking: “What’s the big deal? It’s normal to get stressed over exams. Do we have to teach kids ways of reducing their exam-related stress? They’ll survive.”

From 2012 to 2016, I did quite a shoddy job of responding to my Year 11 students’ emotional needs.

I had a matter-of-fact, “Come on, now. We have a lesson get on with. Let’s focus on the History. You’ll be fine”, dismissive kind of type of attitude.

As a result, I ended up having the same conversations in reaction to my students’ worries and stress, again. And again. And again.

I felt frustrated.

That changed after January 2017.

MOCK EXAMS FEEDBACK LESSON

My Mock Exams, Mindfulness, and Mandarins feedback lesson evolved over the years.

This is the 3-step process I ultimately used to guide my Year 11 (Grade 10) IGCSE History students through the introduction to the mindfulness training part of my mock exam feedback lesson.

You can chop and change the steps to meet the needs of the particular age group, class dynamic, and context in which you are teaching.

STEP 1: RECALLING DETAILS BASED ON MEMORY & A QUICK GLANCE

The purpose of this lesson is to inspire my students to reflect on how they can improve the quality of their focus and revision. But I never say this to them upfront!

I let them get curious. As they walk into the class and see a single mandarin on each desk, I answer any puzzled looks or questions with an “All shall be revealed!” I then ask that they wait until we start the lesson before they touch their mandarin.

I like to start the lesson by saying that we are going to do an activity that might seem irrelevant to their mock exams – at first. But that they will understand why we’re doing it when we’re done. I like to leave a bit of mystery. Keep them guessing. If you prefer a more direct approach, you can explain the purpose of the activity to your students right from the start.

I then ask the students to lower or close their eyes and see if they can imagine a mandarin, in their mind’s eye. I tell them to imagine it in as much detail as possible. They’ve already had a quick chance to at the mandarins as they came and while they waited for the lesson to start. So I find the nods and “yes”-es to confirm they can visualize a mandarin seem quite confident.

I write the words and phrases they come up with for how to describe a mandarin on the board. I tell them we’ll come back to this list after we do another activity where we study mandarin in a more mindful way.

STEP 2: RECALLING DETAILS BASED ON MEMORY & MINDFUL OBSERVATION

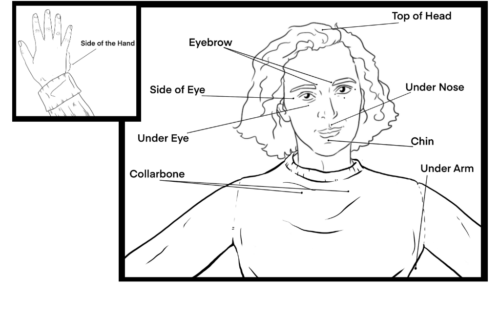

Next, I let them know that they can now touch the mandarin on their desks.

I questions that encourage them to feel the weight of the mandarin, while letting it rest in their open palm. Do they notice that the mandarin starts to feel heavier, the longer they hold it up?

I then ask questions that challenge students to notice nuances in color, shade, shape, and texture. Possible questions include:

- Can they notice any specks of yellow, white, or brown on the mandarin peel?

- If their mandarin has a leaf on it, is the leaf only one shade of green?

- Can they feel the texture of the mandarin, including the texture of the stem or leaves – if it has any? What words would they use to describe each of these textures?

- And what exactly is the shape of mandarin? Is it as round or oval as you thought it was?

This next part is one of my favorites! I challenge them to see if they can peel their mandarin, all in one go. By this time, as you can imagine, they are very focused and present. They have never tried to peel a mandarin all in one go, and they’re wondering if it’s even possible!

I love it when a student claims: ‘It’s impossible!’ I tell them to hold that thought, because we will talk about how it relates to studying for exams at the end of the exercise. At least 2 or 3 students in the class always end up proving this limiting belief wrong. Sometimes the same student will prove themselves wrong by finding a way to peel the mandarin all in one go. And when this happens, I make the most of the teachable moment to do some mindset coaching. Because the ‘It’s impossible!’ mindset is one of the reasons why some students start revising too late. They believe that if they start revising sooner, they’ll forget what they revised. They have a false belief it’s impossible to remember a lot of information unless you cram the night before.

Next, I set them one last challenge – to see if they can eat one piece of their mandarin, slowly. To savor it. Let’s see who in the class can draw it out the longest. I invite them to imagine what it would be like if (for some mysterious reason), all the mandarins on the planet had disappeared! What if this was the last mandarin you ever ate? How could you make it last?

After leading them through this mindful eating exercise using a mandarin, they have another go at listing words that describe a mandarin. I find they are keen to share their newfound awareness of what a mandarin actually looks like.

STEP 3: UNDERSTANDING THE VALUE OF MINDFULNESS FOR STUDYING WELL

I then ask my students to describe the difference between the two lists, so that they see for themselves the impact on the details we write when we mindfully study an object. When we are done writing up the second list of details, we always find that list always ends up being about 3 times longer than the first list…and of much better quality, too!

This is important for the kids who want to get the A*s, As, and Bs to understand. Because to get the top grades in IGCSE History, students writing in exam conditions must not only write thorough answers, in terms of length, but also use precise terms details, examples, and concepts. They need to demonstrate higher standards of both depth and breadth of knowledge. It is upon this foundation of more mindful attention to detail that their ability to write better quality arguments and explanations rests.

We then talk about how the way we study an object (be it a mandarin – or a textbook) has a direct relationship with the quality of our memory of that object, and its contents. This in turn affects the quality of words we use to describe their memories of our studying of that object.

Therefore, studying more mindfully is essential for improving the quality of exam revision, and by extension, the quality of their writing in exam conditions.

THE RESULTS

In the context of the mock exam feedback lesson: Once we finish the mandarins starter activity, I give them time to study and see the parts of their exam responses that I’ve circled that require more attention to detail. When they read the points I make about vague use of terms, word choice, or evidence, they’re now less defensive. What this means is less resistance, and more willing to take the feedback in. As a result, students are more willing to accept the need to change their study habits for the final exam. So in the subsequent weeks, I see more students moving out of the old ‘‘I-must-hurry” mode of revising where they leave it to the last minute, and into a more organized, mindful, focused state of flow.

In the weeks that follow: I find my students are now coming into my class in a calmer state of mind, in that final term leading up to the exams. So the quality of the class environment improves. The lessons flow more smoothly and productively than they did in the years before I started doing this lesson, with fewer exam-stress-related concerns and interruptions.

Also, starting the mock exam feedback lesson with the mandarin exercise helps my students understand the connection between the vague details they might have written in their mock exam essays and the rushed way in which they revised (if their mock exam grades were not what they had hoped them to be). Even if they did great in their mock exams, it helps them see that they can improve the quality of their vocabulary by reducing their stress. Stressing less and focusing more through mindful observation is a win-win situation for them all.

I’ve noticed that after this lesson, most of my students make a more conscious effort to slow down and manage their exam-related stress so that they can revise better and take in more details. They get that they need to spend more time revising so that they can focus more and stress less.

Less haste, more speed.

GIVING CREDIT WHERE CREDIT IS DUE

I’m lucky. I was trained by Christine Counsell as a PGCE and MEd student.

I appreciate Christine for encouraging us to continue our professional development throughout our careers by continuing to read, reflect, experiment, and innovate in our work as classroom practitioners.

Christine also taught us a framework of transferable principles for effective course design. These principles now form the foundation of my practice.

The overarching principle that’s influenced me the most was this: focus on principles for effective course design, rather than on doing the “right” activities.

Why? Because activities come and go depending on what activities are ‘fashionable’ in education at a particular point in time. In contrast, principles stand the test of time.

Another one of the principles Christine taught us that influenced my History course design philosophy was the following: “Build it in, don’t bolt it on”.

In other words, don’t wait until after you’ve taught students the facts to teach them how to analyze those facts. Build the analytic thinking and writing training into the unit, instead of bolting it on at the end.

I’d seen the power of this principle time and again in my practice as a History teacher.

But what I hadn’t done before was to take this principle and apply it for a different purpose: that of building well-being education into my History teaching.

Christine’s teachings planted the seed for me to ask myself, 9 years later, as I ate a mandarin while sitting on my couch on a cold and rainy January afternoon, the big question that ultimately inspired my Mandarins, Mindfulness and Mock Exams feedback lesson:

How can I build well-being education into my History lessons, instead of simply expecting students to bold it onto the end of their school day?

The second teacher who inspired me was Sharon Comberbach, who would come to do Yoga lessons after school, for teachers like me who were interested.

Thanks to Sharon, I learned an activity that would help me introduce Mindfulness into my classroom in a tangible, accessible way.

In the summer of 2016, Sharon surprised us with the fun mindfulness and mandarins exercise I now use in my History lessons. As the activity came to an end, I remember thinking to myself, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could do this exercise for exam students?’

After-school activities like Yoga and Meditation classes are important. But I do believe it’s possible for us, as classroom teachers, to play with ways of building well-being education into our lessons, too.

Our students benefit. And so do we.