Hidden Struggles of International Students: Adversity Amid Privilege

GUEST WRITER: Tanya Crossman is the Director of Research and Education Services at TCK Training. She is currently based in Canberra, Australia, after being displaced from Beijing, China, during the pandemic.

In this article, Tanya reveals statistics that pull back the curtain on the privileged lifestyle of international students to reveal a humbling behind-the-scenes reality that deserves to be acknowledged. Only then can more schools and parents make introducing preventative mental health initiatives a high priority.

Please share this article with parents, friends and colleagues who work in international schools. Help raise awareness about the unique (and often misunderstood) well-being challenges our international students may be experiencing, despite their privileged background.

RESEARCH ON ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS

The first step toward change and healing is understanding the problem. I recently slipped while pushing my four-year-old nephew on the swings, and got the worst sprained ankle of my life! I went to the doctor and had x-rays done, and was told to rest and elevate. Thankfully, I also took my sister’s advice to visit a physiotherapist early on. He diagnosed three torn ligaments, their strength at 20% of normal, and prescribed specific stretches and strengthening exercises. These exercises are not hard to do (one is simply to stand on one leg!) but having diagnosed the problem, he could tell me precisely which motions would help me heal as quickly as possible.

The first step toward change and healing is understanding the problem. This was the spirit behind the TCK Training’s survey of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) among globally mobile Third Culture Kids (TCKs) conducted in 2021. We are all about preventive care, helping parents provide the best environment to protect their children from the difficult aspects of international life.

Our strategies are rooted in research on child development, and our extensive knowledge of TCK experiences – but the research on these fields was always separate – until now. We took the well-researched framework of Adverse Childhood Experiences and applied it to 1,904 adults who grew up with experiences of global mobility.

Our respondents shared their birth year and experiences of mobility, and self-identified their main sector and educational experience. These provided categories by which to sort the data.

Their answers to certain survey questions allowed us to calculate an ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) score for each response.

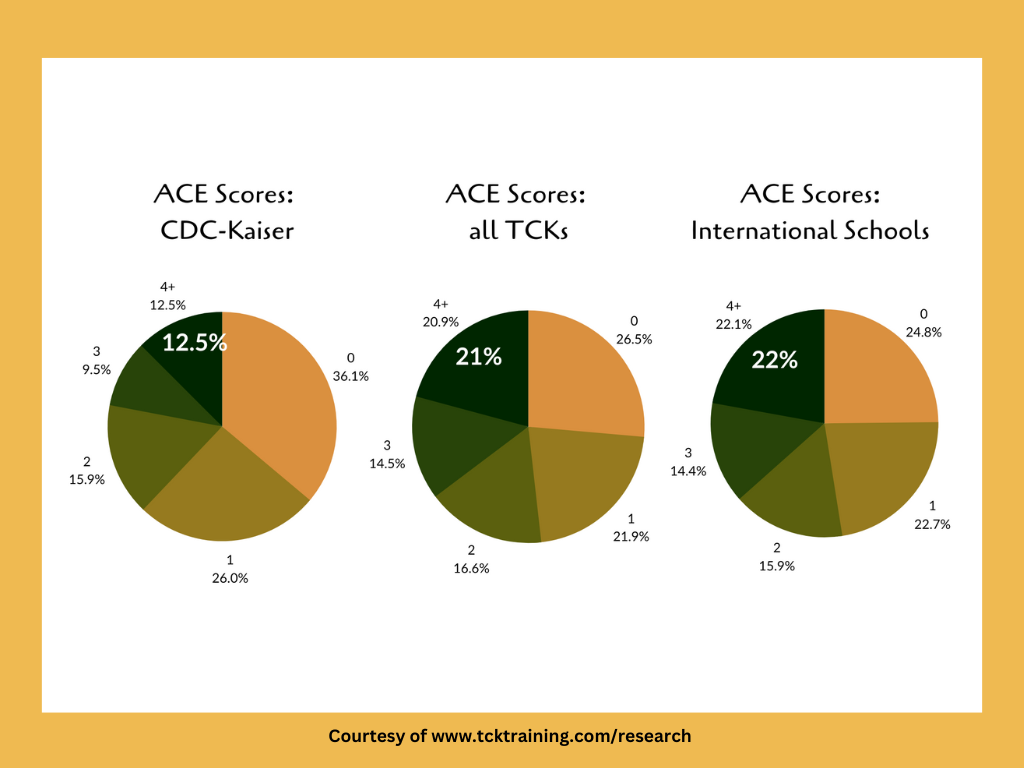

Here is an overview of what we found (see Diagram 1 above):

- 21% of the 1,904 respondents had an ACE score of 4 or higher out of 10. This is significant, as multiple studies have drawn links between ACE scores of 4+ and various negative behavioural, psychological, and physical health outcomes. International school students specifically had a similar rate of 4+ ACEs, at 22%.

- This compares to 12.5% of Americans, and 9% of participants in studies in the UK and the Philippines.

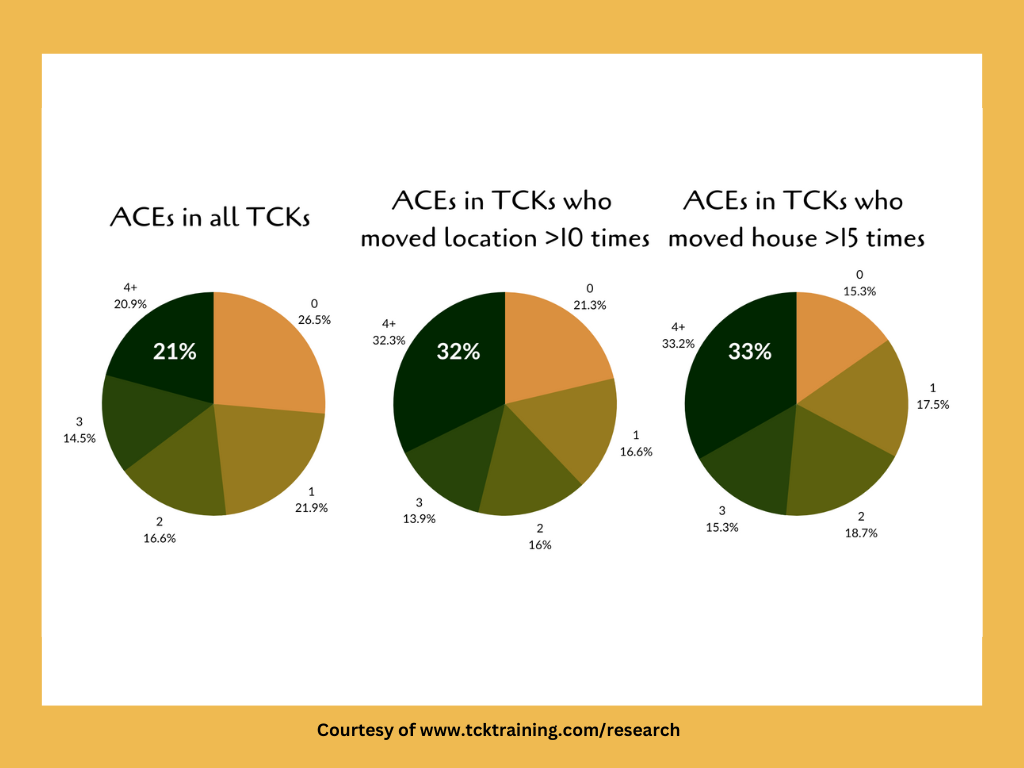

Then we investigated the impact of mobility (see Diagram 2 above).

Among those who experienced extreme mobility in childhood (>10 location moves, >15 house moves), the rate of high-risk ACE scores rose to 32% and 33% respectively.

That means 1 in 3 people who moved frequently are at higher risk.

BUT DOESN'T PRIVILEGE PROTECT INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS FROM ABUSE AND NEGLECT?

One of the reasons these results can be surprising is that the expatriate lifestyle is associated with privilege – corporate salaries, perhaps a housekeeper or driver, tuition at top international schools, and the general glamour of a globetrotting life. High ACE scores in USA-based studies was associated with low socioeconomic status, which is not the case with most expatriate families.

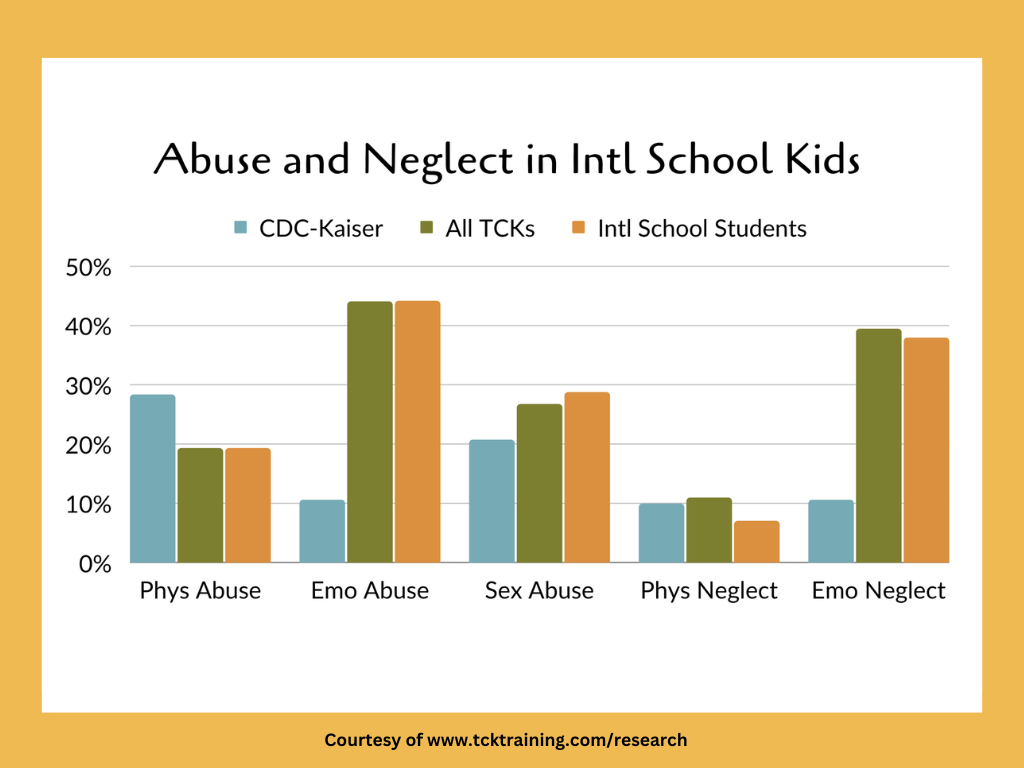

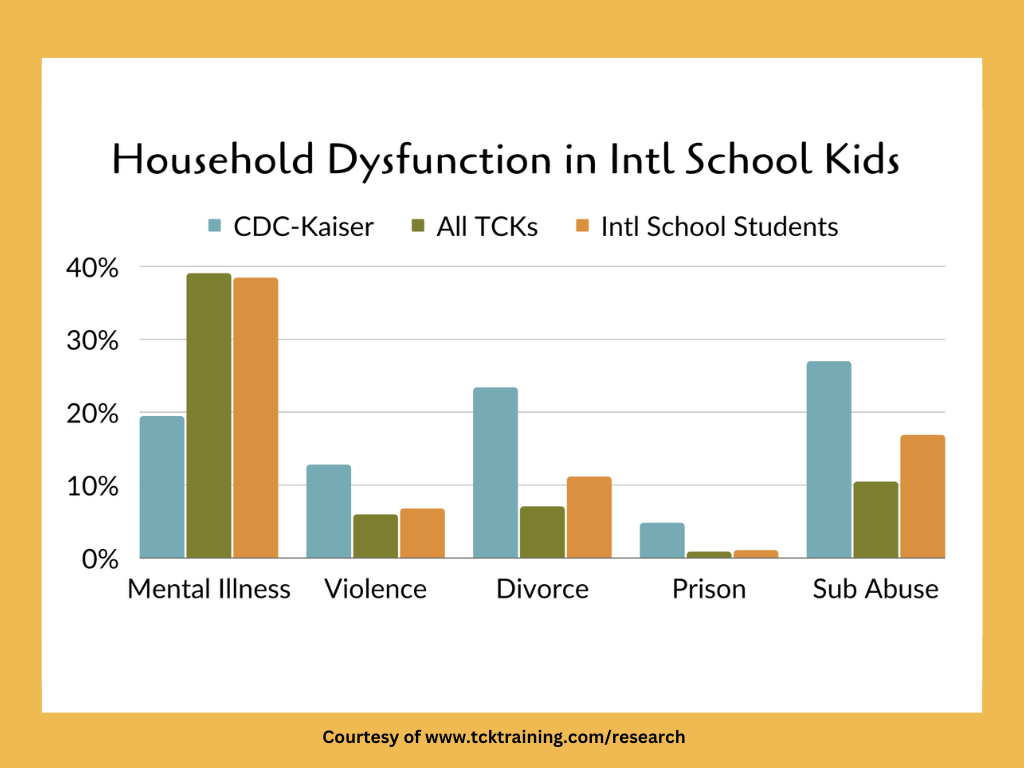

Looking at the specific factors involved in driving the high ACE scores among international school students tells an important story. 6 out of 10 Adverse Childhood Experiences were less common among international school students than among US-based individuals. They were less likely to have an adult household member who was incarcerated or a substance abuser, less likely to have a parent (or step-parent) experience domestic violence, and less likely to have parents separate or divorce. They were also less likely to be physically abused or neglected than US-based citizens.

That being said, 29% of international school students reported experiencing sexual abuse from an adult (or child at least five years older) before age 18, compared to 21% of US-based individuals, but it was the remaining three categories that pushed so many international students’ ACE scores over the 4+ threshold. They were twice as likely to have a mentally ill parent, including depression (38% vs 19%); 3.5 times as likely to experience emotional neglect (38% vs 11%), and four times as likely to experience emotional abuse (44% vs 11%).

These numbers can be shocking, but we titled our white paper “Caution and Hope” for a reason. The good news in all this? These three are the easiest ACEs to influence through awareness, education, and training. International families, and especially those who move frequently or live in communities where friends move away frequently, are under a lot of strain. This is on top of what are often quite stressful jobs, with high expectations of availability outside office hours – at home and even on holidays.

Parents in international communities especially must be empowered to care for their own emotional needs, recognising this as vital for the long-term thriving of their children. Pushing through hurts not only yourself, but also your ability to show up for your children.

SO WHAT CAN SCHOOLS AND PARENTS DO?

Learning how to listen well to children, truly hearing them, giving them safe space to express both positive and negative emotions, and how to process grief together are essential parenting skills that are not innate – they are learned. They are also much harder to practice when we are stressed, such as in the middle of a move – or an airport transfer! Our work is all about both teaching these skills in a non-judgmental setting and also providing practical tools that overworked parents can access, understand, and implement immediately.

Finally, a big benefit of using the ACE framework in our research is that there is also existing research about how Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs) act as a protective buffer, even where high ACE scores exist. In fact, when a child with a high ACE score has most of the 7 PCEs present, their risk of developing depression as an adult drops 72%.

Half of the PCEs occur within the home, and half of them occur outside the home – in community. Children need supportive peers, supportive non-parent adults, and supportive intergenerational communities they can engage with in order to be most effectively buffered from the often inevitable storms of life.

Whether you are a parent or not, there is much you can do to foster protective Positive Childhood Experiences for international school students, and others in the international community.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

- Read Tanya Crossman and Laura Well’s 2022 White Paper: “Caution and Hope: The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids”. References for all studies mentioned in this article are in the White Paper.

- Visit the TCK Training official website: https://www.tcktraining.com/

- For access to the TCK Training’s other 2022 White Paper: “TCKs at Risk: Risk Factors and Risk Mitigation for Globally Mobile Families”.

- For all the TCK Training research: https://www.tcktraining.com/research

- Learn about the TCK Training Elementary and Teen Curricula that provide parents with activities they can do to help improve their kids’ emotional resilience for a globally mobile life: https://www.tcktraining.com/products

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tanya Crossman grew up in Australia and the USA, then lived in China and Cambodia as an adult. She is passionate about encouraging and equipping globally mobile parents in all sectors with all the tools they need to more confidently parent their children internationally, with hope and emotional health. Conducting research to learn about the experiences of children growing up globally is a key part of her work.